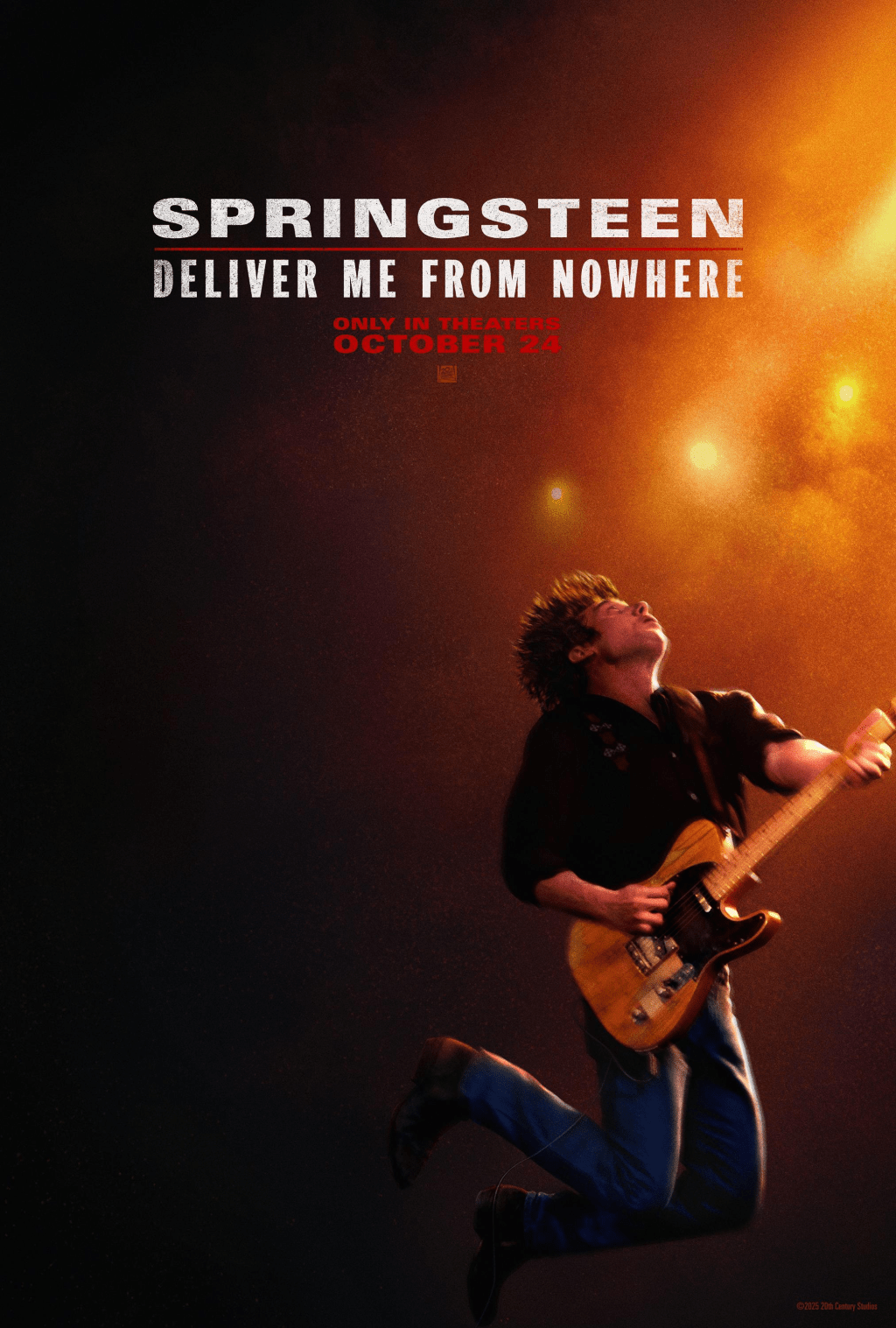

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere is a new film that hit theaters this weekend after premiering earlier this year at the Telluride Film Festival. Written and directed by Scott Cooper, the film stars Jeremy Allen White, Jeremy Strong, Paul Walter Hauser, Stephen Graham, and Odessa Young. It follows Bruce Springsteen, a young musician on the verge of global superstardom, as he struggles to balance the pressures of success with the ghosts of his past.

I’ve never been particularly drawn to Bruce Springsteen’s music. His work clearly has a passionate following, but if I’m being completely honest, I don’t think I’ve ever actually met a Springsteen fan in person. Going into this film, I mostly watched it out of necessity—my schedule in the coming weeks meant this was my only real chance to see it. Between not being a fan to begin with and feeling drained from a long week, I was hoping the movie might jolt my senses and maybe even turn me into a convert. Unfortunately, it didn’t come close to doing that.

It’s difficult not to see Springsteen as an attempt to capitalize on the momentum of A Complete Unknown, especially given that both films fall under the 20th Century Studios banner, now owned by Disney. With their shared studio, musical biopic structure, and prestige aspirations, the comparisons feel inevitable. The film often plays like a companion piece rather than a distinct artistic statement, caught in the gravitational pull of its predecessor’s acclaim. One could easily imagine a scenario in which the filmmakers, consciously or not, aligned their creative sensibilities to fit a burgeoning formula for reverent musician portraits.

For those unfamiliar with Bruce Springsteen’s music or mythology, Springsteen offers little by way of entry. The film opens with impressionistic black-and-white flashbacks to the artist’s troubled childhood—arguably its most compelling sequences—suggesting a psychological framework for his later struggles. Yet, while the narrative gestures toward complexity, it soon rushes past the formative years that might have given weight to its portrait. Instead, the story situates itself at the height of Springsteen’s fame, bypassing the essential groundwork that could have made his emotional conflicts resonate. Devotees will likely fill in those gaps themselves, but for newcomers, the film’s lack of foundation leaves its central figure frustratingly opaque.

If you’ve seen the trailer, there’s a brief exchange in which a car salesman tells Springsteen that he “knows” him, to which Springsteen replies, “That makes one of us.” That line reverberates throughout the film, which intentionally keeps its characters at arm’s length. Rather than grounding us in who Springsteen is at the outset, the film opts to gradually excavate his inner life. The result is a portrait that feels more elusive than enlightening. With its deliberate pacing and competing thematic threads, Springsteen often seems uncertain of what it wants to say—or how it wants to say it.

The film doesn’t arrive at its thematic core until the third act, and even then, its revelations feel somewhat contrived. By the time the narrative pivots toward an exploration of mental health, the groundwork hasn’t been fully laid, making the emotional payoff harder to buy. A late scene featuring Jeremy Allen White stands out, offering a rare moment of raw vulnerability that briefly elevates the film. Yet as Springsteen attempts to resolve the fraught relationship between its protagonist and a family member, the resolution feels more sentimental than sincere. The reconciliation is touching on the surface, but its implications are murkier—suggesting, perhaps unintentionally, that acceptance only arrives once success does. It’s an ending that aims for catharsis but lands closer to contradiction.

For all its structural missteps, Springsteen still boasts uniformly strong performances. Jeremy Allen White doesn’t just play Bruce Springsteen—he seems to inhabit him, capturing the singer’s physicality and restless energy with uncanny precision. Jeremy Strong once again proves to be one of the most reliable supporting actors working today, fully committed even in limited screen time. Paul Walter Hauser provides a welcome burst of charisma, while Stephen Graham delivers a surprisingly tender turn that anchors much of the film’s emotional weight. Yet it’s Odessa Young who emerges as the film’s quiet center, imbuing Faye Romano with warmth and emotional gravity that often outshines the narrative around her.

Much like a greatest-hits compilation, Springsteen unfolds as a series of striking moments that never quite cohere into a satisfying whole. The film sparks to life once Springsteen’s relationship with Faye begins, grounding the story in a rare sense of intimacy and authenticity. The black-and-white sequences remain a highlight, visually and emotionally—the one stylistic choice that feels genuinely inspired. And while the third-act focus on mental health arrives unevenly, it strikes a personal and deeply felt note that lingers beyond the final frame.

Overall, Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere serves as a strong showcase for its ensemble cast, with each performer delivering committed and often deeply felt work. The film’s exploration of mental health provides an emotional throughline, and several individual scenes stand out for their power and sincerity. Yet despite these strengths, the film struggles to offer anything that feels genuinely new within the crowded landscape of musician biopics. Its pacing is sluggish, and the narrative often drifts, jumping between ideas without a clear sense of momentum. For devoted fans, there’s likely much to appreciate in its attempt to probe deeper into Springsteen’s psyche. But for those less familiar—or less invested—the film remains at a distance, admirable in craft but difficult to truly connect with.

VERDICT: 2.5/5 – Okay

You must be logged in to post a comment.